Welcome back to Clothing Inside – a newsletter focused on the ways that clothing is used within, by, and on account of prisons in the United States. This winter, we took a hiatus which we believe afforded us the opportunity to cultivate our approach, and ensure that it is one that both enriches the information we are conveying while authentically communicating the stories and perspectives of people who have experienced incarceration in the United States. With the launch of our GoFundMe (which is still live if you have the means to contribute) we were able to raise some funds so that we could pay those who participated in this month’s edition of Clothing Inside. In that vein, this edition will be focused on the prison economy – specifically, the fashion marketplace on the inside.

While many recognize the exploitative dimensions of prison labor, less awareness exists for the exploitative dimensions of prison consumption. Thinkers like Rosa Luxemburg and Jackie Wang, however, argue that prison labor and prison consumption are linked through their grounding in surplus production1 – a cornerstone of our current capitalist system that not only seeks profit, but also seeks to maximize profit through excess. Carceral structures are the perfect locations to amass a profit in this sector because they utilize populations that our broader society has deemed deficient or unproductive to simultaneously create and consume surplus production. In her book Decarcerating Disability, Liat Ben-Moshe, argues that prisons turn a profit “by transforming ‘prisoners’ into commodities”2; “By clever capitalist alchemy, surplus populations are spun into gold.”3

Here at Clothing Inside, we care about the structural dimensions of prisons, but we think the individual experiences of those inside matter even more. For that reason, we spoke to three people for this newsletter: Laura, Lashonda, and Reese. Laura and Lashonda both share about their time at two women’s prisons: Bedford Hills Correctional Facility and NYSDOC Taconic Correctional Facility, as well as their time at Rikers. Meanwhile, Reese spoke about his time in a New York State facility (NYS) as well as his time in a federal prison in Pennsylvania. These interviews were taken separately, and the answers have been edited for clarity. We would like to extend a special thank you to Hour Children, an organization working to support mothers who have experienced incarceration and their families, for connecting us to Laura and Lashonda.

Can you detail what clothes you were given when you were incarcerated?

Short Answer: It depends on the facility you go to, your gender, and sometimes your religion, but there are some consistencies.

Reese: “When you first come into the jail, they give you I think three sets of clothing. Three pairs of pants, three shirts. They give you a jacket for the wintertime. They give you a sweater. It’s no more hoodies. For the cuttings and stabbings, people would throw on a hoodie, you can’t tell who’s who so there’s no more hoodies. And then they give, I think, three pair of boxers, three t-shirts, three socks. And then you’re on your own.”

Laura: “When I was in Rikers we didn’t wear uniforms. You only wore one when you went on an outside trip. A bright orange jumper that said ‘inmate’ down the back and down the leg in black letters with a big orange coat that said ‘inmate’ across it. It was the most degrading, humiliating thing. Just the bright orange itself with the word ‘inmate.’ Like you just want to announce to everybody ‘stay away this is a piece of crap this is a piece of scum.’ … In State, you get 6 pair of panties, 3 bras and 6 pair of socks. That’s it. And then every 6 months you can get more. You would get 3 pair of pants. A set of skorts which came below the knee. You get 3 state shirts. You get 2 sweatshirts. 1 coat, 1 bath robe, 1 pair of pajamas, 1 night gown, and they just started issuing t-shirts the year before I left. You were entitled to 3 green t-shirts and the white one. The green ones were decent, everyone was wearing them. The white ones were made by Corcraft who makes all the State clothes. And Corcraft is made by inmates.”

Was that enough?

Short answer: What was given was uncomfortable, and didn’t adequately provide protection.

Laura: “The clothing was hard. Very stiff material. And with the clothing you froze in the winter time. Especially with their jackets. When I first got there, the jackets were a little thicker and they had a lining. Now it’s like a piece of paper. You freeze… I was lucky I had people sending me sweatshirts and sending me thermals and things like that so I was able to keep warm. But if you had to rely on just the state clothes you were gonna freeze to the death! And they give you one knit green hat. They don’t provide you with thermals – that’s only if you work at certain jobs like the yard crew. And the boots that they have you wear and the sneakers! Ugh don’t even let me get into that! I swear the sneakers are so rotted that I think they have dry rot because you could push your finger in and the material just comes apart from the sole. Now every nine months, you could get a new pair, but people fought it because within three months you had big holes in the bottom of your sneakers. And the boots, there’s no treading on the bottom. My friend who worked in the mess hall slipped and hurt herself because there’s no support”

Lashonda: “The undergarments, they were really cheap. They would tear after one use. I personally liked the socks because they were long and they came all the way to your knee so they were good for the winter time. You put that on with your long johns and your legs were not cold … The boots were so horrible they hurt your feet so bad. I think they were from Corcraft too — they were like these fake Timbs looking boots. They were just so hard. So some of us would take maxi pads and put them inside to give us some comfort inside the boot.”

How were you able to get other items?

Short Answer: Commissary (mostly.) Sometimes external organizations helped.

Reese: “You can buy sweatsuits at commissary, you can buy long johns at commissary, you can buy socks. So you’re going to buy what’s needed to keep you warm. You just gotta pay for it.”

Laura: “When you first come in, they give you a couple of bars of Corcraft soap. The soap turns your skin colors! It’s just horrible and you can’t use it on any private areas; it is gonna burn you! But commissary started selling Dove and they sell some other soap. But some people don’t even get enough money to buy Dove soap. So one time when I had gotten my income tax when I was in Rikers, I remember I bought all this soap and deodorant and everything and I made care packages for everybody that came in ‘cause I knew what it was like. … we also had a thing called ‘The Help Fund’. If you earned less than $10 a month, you could write to them and they would supply you with soap, shampoo, conditioner and brand name stuff because it was donated. But if you made $11 (a month), you weren’t getting any of that … And then the donations started disappearing, and then they were giving out those little travel size shampoos and soaps. But then you would get some organizations at like Christmas time or Easter time donating these bags of soap and shampoo, conditioner, wash clothes, real deodorant.”

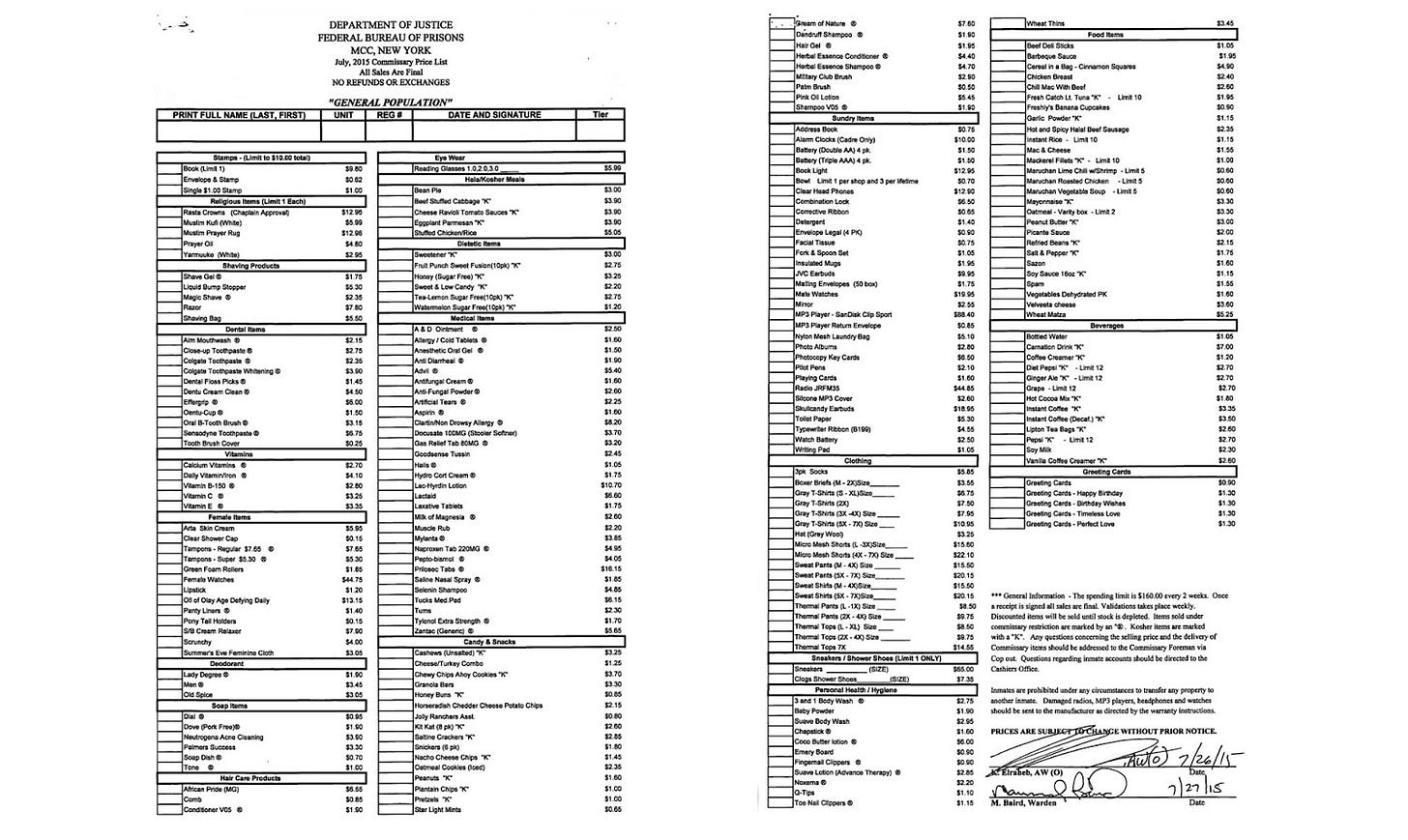

How is commissary different from a general store on the outside?

Short Answer: Your money doesn’t stretch as far, but you also don’t need to worry about the same costs of living as you would otherwise. Outside help really makes all the difference.

Lashonda: “Alright, let’s say I was making 16 cents. So that would be maybe every two weeks $10 and some change, maybe even $20. And then you’re trying to get commissary food plus hygiene — then it’s like really crazy. Like a box of chicken was maybe $4-$6 plus change. A bag of 1 lb rice was like $1.04. Then you have to get your seasonings and your vegetables and then you gotta get your hygiene… $20 is not gonna do you no good. … If you don’t have help on the outside then you’re really, really struggling inside there.”

Reese: “The difference was, I wasn’t spending my money when I was locked up (laughs), so I’m spending my money now. So when I was locked up, I didn’t look at the value of the price. I didn’t care. I wanted it, I needed it, I’m buying it … I’m not paying rent, I don’t have no real responsibilities … you’re only getting money just to survive. Majority of the people did the bid with me, so I had a nice little support system (…) It made a great deal of difference. It takes the stress off of you … you gotta make sure that you have a support system. If you don’t have a support system you’re going to be lost in the jail system.”

What does support and solidarity look like inside?

Short Answer: A lot of different things to a lot of different people.

Reese: “In the State, I can’t remember the amount of sneakers you can have, but I remember I had nine pairs at one time. And they came and searched my cell, and it was ‘oh, you’re only supposed to have four pair of sneakers.’ And from that day on, when they did the search, I used to have people that didn’t have a lot of sneakers hold them. You know, hold this pair, hold this pair, hold this pair (laughs). So they won’t take them. Or make me send them home … Whether we’re black or spanish or white, we all have one thing in common – we all against the police. If the officers are coming for a search, and this is your possession and you don’t want them to take it, at the end of the day we’re all convicts so, you know, if you say ‘yo hold this until the search,’ and it ain’t something to get them in trouble, like a pair of sneakers where the police is just going to count them … I’ve never been told no, even to the person that I’ve barely said hi to.”

Laura: “I enjoyed working in laundry because I used to do things that I wasn’t suppose to do like give out extra underwear, extra socks, extra bras. Because I knew how crappy all the stuff was. I mean the panties are a piece of crap! Half of them the elastic is all stretched out when you get it. And you only get new panties every 6 months … One officer at Bedford had compassion. And I know for a fact that when some girls in the units that he worked on didn’t have things, he’d give them bars of soap or things like that. There are certain officers that are nice like that. If they got caught they’d get in a lot of trouble but I mean for hygiene they would do it. Or they would ask me ‘Laura, do you have some soap that you could donate to whoever whoever?’ And I’d be like ‘yeah don’t let her know it came from me.’ Because it might make her feel bad, so I’d say, ‘you know, you give it to her. Tell her it’s from you.’ But there are some officers with compassion. Majority, no. But there are some.”

What was it like shopping again when you came back home?

Short Answer: A mix of emotions.

Reese: When I first came home in 2018, I went to the halfway house in the Bronx, and these 11s drop. I remember my sister coming to see me, and she says, do you want something to eat? And I say, listen. I just heard the 11s is dropping (laughs). I need those. ‘You can’t be serious’ – yes, I am serious, I need those. When I was young, I always used to see – whether it was my friends or kids that I grew up with – with the latest sneakers. And as I got older, and I started doing crime I just got heavy on sneakers … I love fashion. So, I guess, I don’t change whatever my circumstance is, or whatever situation I’m in, I’m not changing my fashion. Just because I’m in jail, I don’t think I should stop being who I am”

Laura: “Before I got incarcerated I had a job where I was wearing suits to work. So I used to like to dress up and wear my heels and everything … Now, 17 years later, I can’t even walk in heels anymore. From not having them on for so long. My friend bought me a pair of these wedges that the heel was about this big (shows about an inch with her fingers) and I can’t walk in them. I’m like, look what prison did to me – I was crying (laughs). And you know what, when I came home and I went shopping I said everything that I want to buy is blue, black, and gray because those were the colors that we couldn’t wear when we were inside … I will never wear green again. I said the only thing I wanna see that’s green when I go home is the grass under my feet and the money in my pocket (laughs).”

x

The Curatorial Team

Have questions or recommendations for the team at Clothing Inside? Contact us at clothinginside@substack.com. Want to help us commission writers, artists, and designers that have been affected by incarceration? Please visit our fundraising page.

A big thank you to Reese, Laura, Lashonda, and the folks at Hour Children for their time in this issue!

Jackie Wang, in her book Carceral Capitalism, lays out the economic structure underpinning American Prison systems by writing about the debt economy, municipal finance, juvenile criminal justice, algorithmic policing, and e-carceration. In it, she references the philosopher activst Rosa Luxemburg by saying, “But ‘who, then, realizes the constantly increasing surplus value?’ In Luxemburg’s view, it is consumers outside the domain of the formal capitalist sphere who prop up the capitalist economies by absorbing the surplus production of both consumer goods and the means of production.” See pages 105 and 106 for this reference.

Liat Ben-Moshe, in her book Decarcerating Disability: Deinstitutionalization and Prison Abolition, explores the potential pathways of prison abolition by looking at the deinstitutionalization movement in the United States. In it, she makes the comment, “The prison-industrial complex profits from racialized incarceration by transforming ‘prisoners’ into commodities and by the construction and maintenance of prisons by construction companies as well as suppliers, catering, and telephone companies.” See page 12 for this reference.

Ben-Moshe, Decarcerating Disability: Deinstitutionalization and Prison Abolition, pg. 13.

So informative, so well thought out, so important — thank you x