Welcome back to Clothing Inside–a newsletter focused on the ways that clothing is used within, by, and on account of prisons in the United States. This month’s newsletter is using the orange prison jumpsuit to focus on representations of prisons in the United States, and their relationship to the realities faced by incarcerated people. Since you’ve made your way here, we wanted to thank you for giving our newsletter a chance, and for giving your attention to the cause. If you’d like to stay up-to-date with our newsletter and upcoming exhibition, Reclaiming and Refashioning the Carceral Body, you can subscribe below. If you’d like to help us commission writers, artists, and designers that have been affected by incarceration, please visit our newly launched fundraising page. To read the full article please be sure to click the link to our website.

Representations

“The jail you see on TV is nothing like the jail in real life.” (Ms. Blue - Ladies of Hope House Ministries).

While the broader public has undoubtedly come in contact with representations of prison attire in costumes--for television or events like Halloween--much of our understanding about the reality of prisons is clouded. Certain prison mythologies have become a point of reference for the public imagination, like the acclaimed prison dramedy Orange is the New Black (OITNB) which depicts author Piper Kerman’s time in federal prison at FCI Danbury in Connecticut. While the show is loosely based on Kerman’s real experience inside, it is limited in its ability to holistically portray the experience of the 1.8 million people that are currently incarcerated in U.S. prisons and jails. Ms. Blue, a former patron and “house mom” at The Ladies of Hope House Ministries’ co-living space, served time in multiple state prisons across the state of New York when she was incarcerated. She shared that much of what is depicted in the widely popular prison show is not at all in alignment with her reality: “It’s not like State time though... State (prison) is worse.” Oftentimes in the quest to package the prison experience for mainstream consumption, articulations of the prison experience can become warped, as they tend to adhere to the archaic motifs that the general public associates with prison. This distinction between reality and representation is particularly salient in one clothing item: the orange prison jumpsuit.

The orange prison jumpsuit has become an emblem of the U.S. prison system. Despite the fact that Jennifer Rogien, the costume designer for OITNB, incorporated comprehensive research into her costuming for the show that complicates perceptions of prison dress, the advertising images and program title still reinforce a connection between the color orange and the experience of incarceration. Even out-of-costume editorial photographs of the cast reinforce this association, as fashion publications have photographed the ensemble in orange dresses or jumpsuits to signify their relationship to the show.

Realities

In reality, most prisons don’t utilize orange jumpsuits; dress requirements in U.S. prisons and jails vary depending on the facility type and the location and utilize “a diverse array of jumpsuits, scrubs, fatigues and denim”1 . In New York prisons, for example, it's more common to find people clothed in either hunter green or khaki uniform top and pant sets. Why is it, then, that the orange jumpsuit is understood as the current standard for penal dress practices across the U.S.? Dress and Textile Design Historian Juliet Ash makes the case that this phenomenon--the recognition of the orange jumpsuit as the dominant uniform in different mainstream media across the US--is a result of particular symbols of criminality being pushed forward by mainstream media.2 Ash argues that this process affects our expectation of how an incarcerated person should look, which consequently affects our expectations of how an incarcerated person should be treated. Thus, the ubiquity of the orange jumpsuit determines what kind of bodily punishment we determine is permissible for those individuals adorned in symbols of criminality.

Juliet Ash asserts that the clothing of incarcerated people were historically only publicized in moments when it was “politically strategic” for the government to make these punishments publicly visible. The major shift in the US took place in 2001 with the start of the U.S. War on Terror when “people around the world who had access to the media of any description ... knew the inmates at [Guantanamo Bay and secret prisons around the world] wore hoods or the orange jumpsuit.”3 As a political tool, this uniform can serve a multitude of functions. As a direct tool of punishment, it has the potential to not only evoke feelings of humiliation and shame, but to make that shame and humiliation visible. When thinking of the impact that shame has on one’s ability to move beyond the trauma both that they’ve caused and have experienced (especially as we consider it in the context of prisons), the founder of Broken Crayons Still Color, Toni Collier, talks about shame saying, “Shame keeps us closed up hiding from people, hiding from authenticity and it robs us.” This weaponization of shame has great personal consequences, but also frames an individual’s humanity as being directly connected to their perceived innocence. The orange prison uniform is, in this way, punitive rather than rehabilitative -- there is no potential for remorse within this mode of thinking. Elspeth Van Veeran, whose research centers around U.S. security cultures and policies specifically in relation to the U.S. War on Terror, notes that the orange prison uniform has the ability to reduce a person’s identity so that they can be placed “into the machinery of incarceration as an identical and interchangeable component.”4 The orange prison uniform, therefore, not only functions as a tool for prisons to punish, but as a tool for prisons to use people as a means of production. While the state utilizes the orange prison jumpsuit to mark particular bodies for systems of production -- and, ultimately, profit -- it simultaneously uses the orange prison jumpsuit to cast these bodies as criminal, incompatible, and “Other.” Van Veeran insists that, “[a]s objects familiar from U.S. prison culture, these suits act as the ‘design equivalent to a continuous state of red-alert,’ visually emphasizing the danger posed by crime regardless of proof of culpability.”5 This uniform becomes a weapon in itself, as it designates particular bodies -- “enemies of the state” -- as worthy of the most grotesque forms of punishment possible.

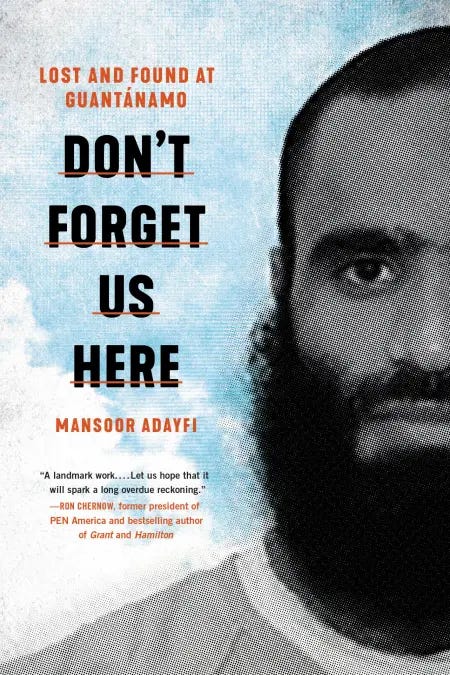

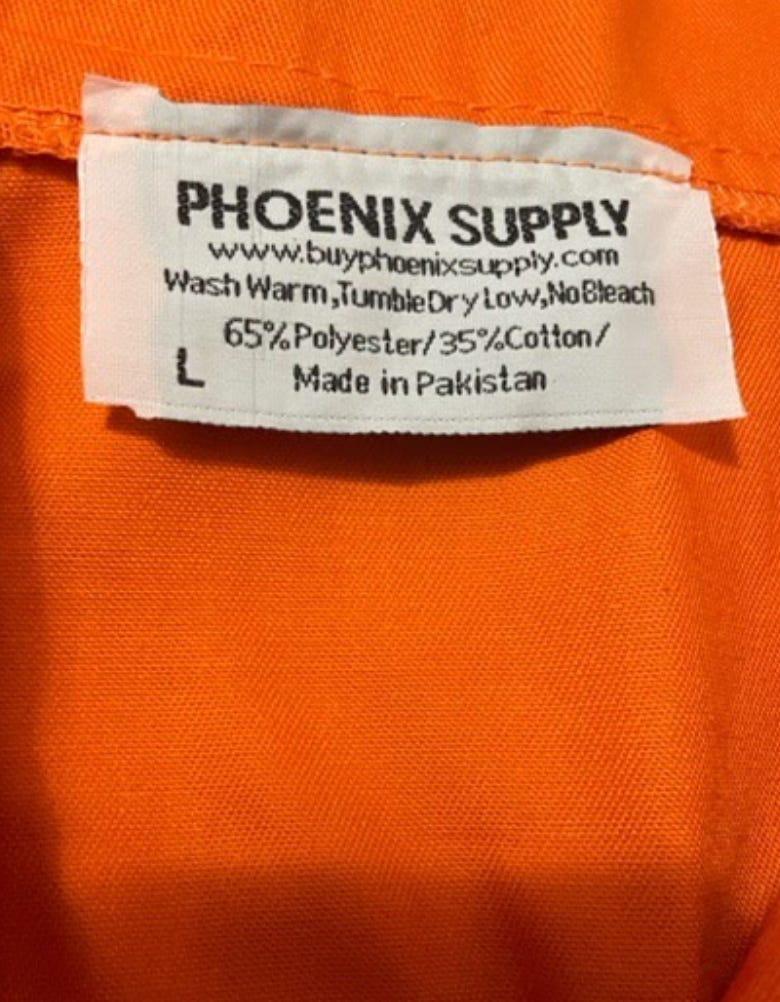

These punitive measures imposed by the prison uniform are not just symbolic, however, as the prison uniform has material consequences as well. The uniforms required by prisons are mass produced, and tend to be ill-fitting for many people inside. Beyond being uncomfortable, this sizing can have health consequences -- some women have told us about skin conditions that they have developed on account of poorly fitting bras, and about difficulties they face keeping clothing clean during their menstrual cycles because their undergarments were far too large. Then, there are other cases where clothing is restricted altogether as a means of punishment and brutality. Mansoor Adayfi -- a writer, advocate, and former Guantanamo detainee -- details many instances where this was the case at Guantanamo Bay Detention Center. Early on in his book, Don’t Forget Us Here, he details a conversation he had with the camp commander in which he told him “We are modest … you make us strip in front of women … you know it's against our religion, but you still do it.”6 While Adayfi’s experience is unique to being held at Guantanamo, the experience of going without clothing while incarcerated is not. For those familiar with the current crisis on Rikers Island, you won’t be surprised to know that involuntary nakedness has been the experience of some who are speaking out about the current conditions at the notorious jail. In an article published last month by New York Daily News, a person being held at Rikers stated that he was forced to sleep naked in sewage-like-conditions because he had not been issued a uniform or anything else for clothing (NY Daily News). This is a global issue that spans decades: lack of adequate clothing and footwear has fatal consequences.7 The material conditions of prison clothing aren’t simply aesthetic -- they’re a matter of human decency, and a matter of life and death.

Corporate Involvement

Today, there are only a handful of corporations that are in the business of servicing prisons. One of the household names in corrections supply distribution is Bob Barker Company, which “has been awarded at least $13 million in federal prison system contracts since 1995, including agreements with about 100 federal prisons across the country” (Truthout). “For nearly 50 years” - the website reads - “Bob Barker has introduced many new, innovative products to help solve customers’ problems and make corrections and detention facilities safer.” Yet, as one makes their way through the company website, a question may come to the fore: who is the customer for whom Bob Barker is making corrections and detention facilities safer? Is it incarcerated people? Are Bob Barker’s cotton-polyester uniforms -- which are not only harsh on the skin but also lacking in weather durability for cold weather in locations with historically inadequate healthcare treatment -- making incarceration safer for incarcerated people? Are incarcerated people the focus when Bob Barker’s uniforms are only available for purchase by pre-approved “federal, state, local government agencies & select businesses,” and not accessible to the broader public? These corporations make their profit by servicing the prison system, not by designing for the people inside.

Activist Involvement

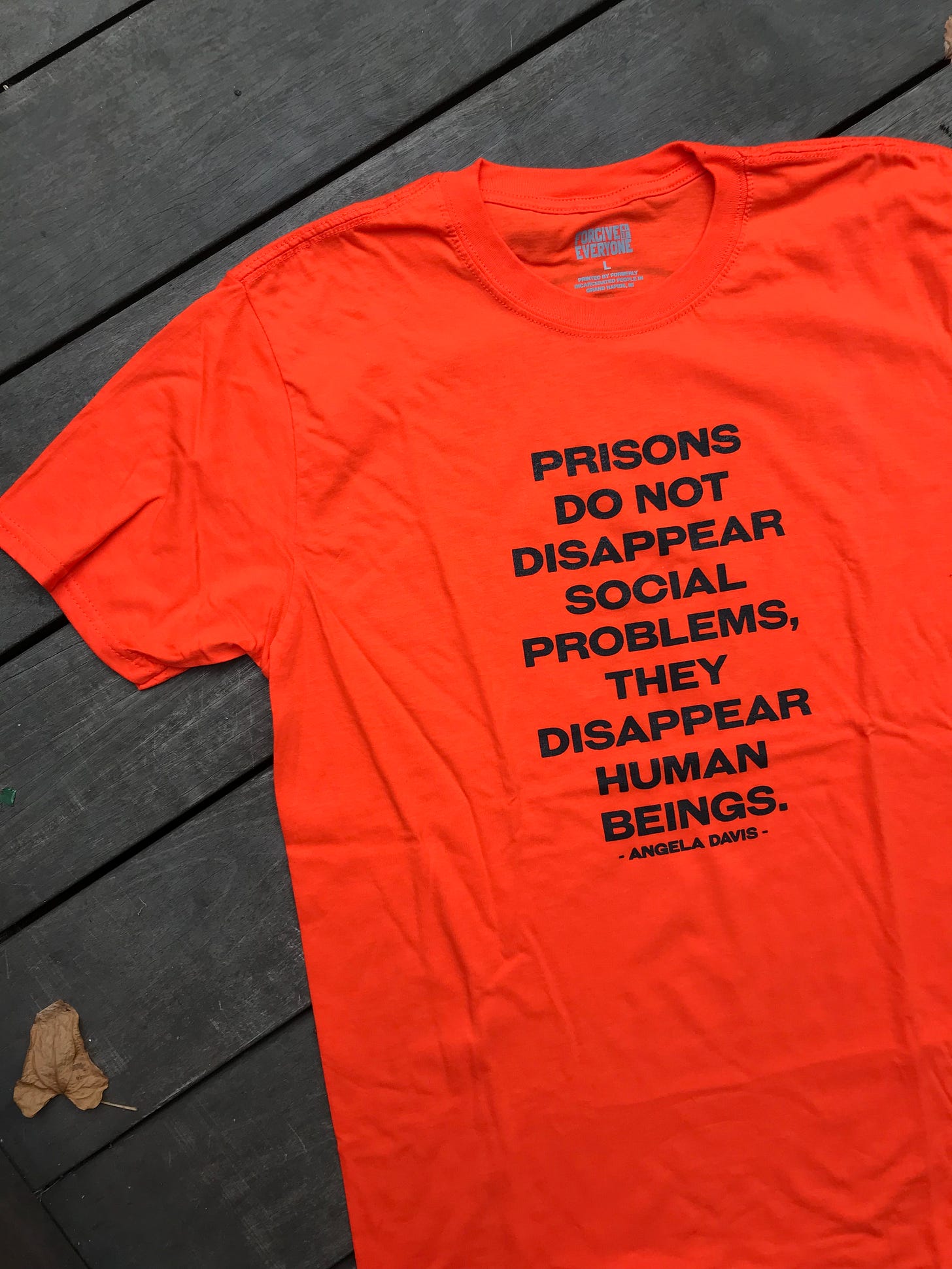

While the state has undoubtedly utilized the orange prison jumpsuit to bolster its power to the detriment of those incarcerated, there are complications in the state’s ability to determine the orange jumpsuit’s meanings. The aforementioned researcher Elspeth Van Veeran specifically refers to activist interventions within Guantanamo Bay Detention Camp and within the public sphere -- like a shirt-tearing protest led by Ahmed Errachidi inside Guantanamo and a public protest staged by Terry Hicks in which he wore an orange jumpsuit and locked himself in a cage on Broadway in New York City on behalf of his son -- that utilize the orange jumpsuit for protest.8 These are not the only times that the orange jumpsuit was used for civil disobedience inside Guantanamo; Mansoor Adayfi has indicated that “[a]ll we had in our cells were our orange uniforms, thin plastic ISO mats, flip-flops, and some of us had one towel,”9 and so it has functioned as a recurring tool for the men incarcerated there. Sherill Roland, the artist behind The Jumpsuit Project, brings the orange jumpsuit into public space as a method of creating spaces for conversation where audiences can challenge their presuppositions about mass incarceration. Jacques Agbobly similarly utilized clothing to comment on carceral presuppositions in their graduate collection at Parsons, the New School. While a range of themes and cultural codes lace their work, one stands out in our minds: they incorporated orange heavily in their collection both to “subvert the narrative around the color orange and incarceration” particularly as it applies to the dress practices of Black men. Our friends at For Everyone Collective -- an abolitionist screen printing collective -- sell one shirt, the Free Angela Tee, in the notorious orange color. With the words “‘Prisons Do Not Disappear Social Problems, They Disappear Human Beings.’ - Angela Davis” written across the front, this usage of orange acts as a tactic to force viewers in public spaces to look at the abolitionist idea. And, as previously mentioned, film and television like Orange is the New Black has used the orange prison jumpsuit as a tool in a quest to complicate cultural understandings of prison. As does woman prisons activist Mary Enoch Elizabeth Baxter whose lyrically focused music video speaks on the traumas of having to give birth behind bars while wearing an orange uniform, wrist and ankle shackles.

There is evidence that these activist interventions have tangible outcomes, as their public visibility has pressured prison officials to lessen, or altogether abandon, the use of the orange jumpsuit in U.S. prisons. John B. Bellinger III, Legal Adviser to the Secretary of State, stated that the public visibility of the orange jumpsuit caused an administrative shift in the uniforms used in Guantanamo: “we have gone along making many changes in Guantanamo that simply have not been noticed. Very few people wear orange jumpsuits anymore, and yet that is the image that is being left with people all around the world, that everybody in Guantanamo is wearing an orange jumpsuit, kept in solitary, and wheeled off on gurneys to be interrogated or tortured. . . . the United States has had a very difficult [time] trying to correct these misimpressions.”10 While this statement may not be wholly accurate as it undoubtedly was made to fulfill a PR agenda, it provides a larger revelation for our research: the orange jumpsuit may be a tool employed by the Prison Industrial Complex to punish, deindividualize, and stigmatize incarcerated people, but critical interventions with the uniform have the ability to delegitimize its usage.

Furthermore, as we try to separate fact from fiction as they relate to carceral experiences, it becomes clear that one source offers more than any other: the community. While theorization may offer us a framework for interrogating the foundations of the prison system, the insights offered by incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people are the only way we can understand the material conditions inside. This reality is obscured -- by both the state and by the corporations making a profit -- and the testimony of people inside is critical if we are ever to grasp the machine of mass incarceration.

x

The Curatorial Team

Have questions or recommendations for the team at Clothing Inside? Contact us at clothinginside@substack.com. Want to help us commission writers, artists, and designers that have been affected by incarceration? Please visit our newly launched fundraising page.

A big thank you to The Ladies of Hope House Ministry and Mansoor Adayfi for their time in this issue!

Fashion, Style & Popular Culture, is an academic journal that specifically focuses on the field of fashion studies and its engagement with popular culture. Heather Akou’s essay, “Prison Uniforms on the Outside: Intersections with US Popular Culture,” appears in Volume 7, Number 4. This essay specifically hones in on American engagements with prisons both through the consumption of popular culture images, as well as through active participation in dress practices that are influenced by incarceration. See page 474 for this reference.

Juliet Ash’s Dress Behind Bars articulates the historical lineage of prison dress practices globally to inform our understanding of the impact that the uniform plays in the experiences of the incarcerated. She examines how over time the prison uniform has evolved in an attempt to “reform” this system and to move away from a system centered on punishment to a system more aligned with rehabilitation. In her tracing of prison dress history she communicates how the quest for reform has not been linear and in fact has backpedaled to more archaic practice throughout its evolution. While she looks globally at prison dress practices, her primary focus is on the US and UK’s relationship with prison uniforms.

Juliet Ash’s Dress Behind Bars, pg. 157

Making Things International 2: Catalysts and Reactions, is a book that conceptualizes the political assemblages behind various material objects. For this newsletter, we specifically pulled content from Elspeth Van Veeran’s chapter, “Orange Prison Jumpsuit.” Here, she rationalizes her decision to focus on the orange jumpsuit because “clothing makes meaning as it connects with the bodies that wear it.” See page 125 for this reference, which features a quote from Allen Feldman’s Formations of Violence.

Van Veeran, Making Things International 2: Catalysts and Reactions, pg. 126

Don’t Forget Us Here, is a memoir by Mansoor Adayfi that details the experiences he had while detained at Guantanamo Bay Detention Center for fourteen years. While the story undoubtedly sheds light on the atrocities committed against those incarcerated at Guantanamo, it also celebrates the resilience of those that are fighting to survive in these horrific conditions, and honors their humanity through a complex rendering of their multidimensional lives. Adayfi undoubtedly has a gift in finding and translating beauty, even in the bleakest of circumstances. See page 36 for this reference.

Juliet Ash’s Dress Behind Bars, pg. 145

Van Veeran, Making Things International 2: Catalysts and Reactions, pg. 129

Adayfi, Don’t Forget Us Here, pg. 156

qtd. Van Veeran, Making Things International 2: Catalysts and Reactions, pg. 133